- Home

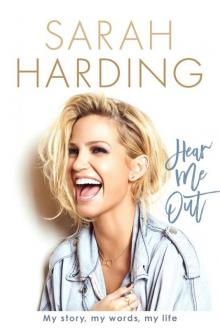

- Sarah Harding

Hear Me Out

Hear Me Out Read online

Sarah Harding with Terry Ronald

* * *

HEAR ME OUT

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

CHAPTER 16

CHAPTER 17

CHAPTER 18

CHAPTER 19

CHAPTER 20

CHAPTER 21

CHAPTER 22

CHAPTER 23

CHAPTER 24

CHAPTER 25

CHAPTER 26

CHAPTER 27

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

One fifth of Brit-award-winning pop group Girls Aloud, singer Sarah Harding was part of the UK’s biggest selling girl group of the 20th Century. With 8 million record sales, the band also achieved a run of twenty consecutive Top 10 singles in the UK charts. Before fame beckoned, Sarah toured the North West of England performing at social clubs and pubs. Her first foray into acting came in the BBC TV film Freefall, where she played the beautician girlfriend of Dominic Cooper. Sarah also had a starring role in St. Trinian’s 2: The Legend of Fritton’s Gold and went on to have a leading role in Ghost: The Musical. Outside of acting, Sarah was crowned the winner of the 20th series of Celebrity Big Brother.

Hear Me Out is her first and only book.

For my mum

Thank you for all your support and love

And for putting up with me

Love you x

Permission and Picture Section

1 © Shutterstock

2 © Shutterstock

3 © Sarah Harding

4 © Polydor

5 © Shutterstock

6 © Sarah Harding

7 © Sarah Harding

8 © Polydor

9 © Polydor, except top left © Getty Images; © Polydor’ except middle left © Getty Images

10 © Sarah Harding, below middle © FameFlyNet and row 4 far left © Shutterstock

11 © Shutterstock

12 top right © Peter Loraine, middle © Sarah Harding, middle © Camera Press, below © Terry Ronald, right © Getty Images

13 © with kind permission of Sarah Harding fans

14 © Sarah Harding

15 © Channel 4

16 © Shutterstock

17 © Shutterstock

18 © Getty Images

19 © Shutterstock

20 top © Getty Images, middle © Sarah Harding, below © Shutterstock

21 © Sarah Harding: © Elisabeth Hoff

This book is a work of non-fiction based on the life, experiences and recollections of the author. In some cases, names of people, places, dates, sequences and the detail of events have been changed to protect the privacy of others.

PROLOGUE

It’s strange, this world I find myself in. It’s like I’ve stepped on to another planet where everything seems unfamiliar. I suppose everybody could say that in the midst of a global pandemic, but that’s not it for me. As I write this, it’s a few weeks before my 39th birthday, and I have no idea what’s waiting for me in the year to come. Nothing is certain any more.

As most of you will know, I have cancer. Cancer that has spread from its original site in my breast to my lung, making it much harder to treat. I’m doing my absolute best to be positive and to fight it. Still, it seems that, even with the best immunotherapy, I’ll be looking at two years maximum.

As those of you who have been through something like this know, some days are easier than others. During my ongoing chemotherapy treatment, I have good days and bad days.

On the good ones I find myself getting a bit restless, not knowing what to do with myself. I have a busy mind and always have had; that’s one of the reasons I decided to write this book. It’s given me something positive to focus on. It’s also a chance to reflect on everything, good and bad, and to remind myself what a wonderfully full and colourful life I’ve had up to this point. A life I’m very grateful for, having achieved above and beyond anything I dreamed of when I was a little girl.

The other reason for writing my book now is that it’s, I suppose, a way to set a few things straight. Everyone has an opinion, that’s a given, and I imagine most people picking up my book will have an opinion about me – some good; some maybe not so good. We all make judgements about people we think we know; it’s human nature. I can’t rewrite history; all I can do is be as honest as I can and wear my heart on my sleeve. That’s something that hasn’t always worked out for me in the past, but it’s really the only way I know.

I’ve done my best to be honest and get it all down, although it’s probably better that I don’t tell you absolutely everything now – otherwise, there’ll be nothing left to put in a sequel!

One of the things I’d like to achieve with my book is to show people the real me. Or perhaps remind them. I suppose that’s one of the reasons many people write an autobiography, but for me it’s especially relevant. When I look back at my time in Girls Aloud, I feel like I became a caricature. OK, so maybe I put out a particular image, which the press and media latched on to. It was an easy one to work with: rock chick, blonde bombshell, party girl, the caner of the band. For me, it was like, ‘Oh! That’s who I am then. I’ve been looking for my role in the band, so this must be it.’ So, in that respect I suppose it became easy for me as well. Convenient. I mean, I liked a drink, I was a bit rebellious, I liked to go out partying, so it was a win/win. Until it wasn’t.

Somewhere among the nightclubs, the frocks and hairdos, the big chart hits and the glamour of being a pop star, the other Sarah Harding got utterly lost. I’m saying the other Sarah rather than the real Sarah because there is most definitely that fun, crazy party girl in me – there always was. It was the other Sarah – the one who liked curling up at home with her dog and a good book; the one who enjoyed cooking a roast dinner for her friends; the one who liked spending nights alone, writing songs and making music – who got lost. She’s the one who’s been forgotten. Yet she’s still here. She’s right here talking to you now. And all she wants is for you to hear her out. Now more than ever: hear me out.

CHAPTER ONE

What do little girls dream of becoming? Princesses? Politicians? Athletes or astronauts? Nurses or mothers? All of the above, I suppose, depending on the little girl. Well, my dream was crystal clear from the start. I wanted to be a pop star. Wait, that’s not exactly true. Not a pop star – a singer. I wanted to sing, and I wanted people to hear me sing. I wanted to perform and to have everyone watch me. At family gatherings, when I was little, I gave performances for my parents and anyone else I could get to watch.

‘Now sit down, everyone,’ I’d say, ‘I’m about to sing.’

Only it wasn’t that simple. It wasn’t just that I wanted to sing for people – I also wanted to get some kind of reaction to what I was doing; for people to think I was good at it. I wanted to be loved and accepted.

I suppose that’s all I’ve ever really wanted.

As I got older, music and singing continued to dominate my childhood dreams. My dad, John, was hugely into music. A talented musician in his own right, he played lead guitar, piano and bass, and he sang too. I vividly remember the photograph of him and his guitar, which was on display at my granny’s house. Dad has been in quite a few bands over the years, and one of the things we have in common is that we’ve both performed at The Royal Variety Performance and met the Queen. How cool is that?

I was never what you

’d call a girly girl, even back then. That said, I enjoyed art and drawing very much. One of my early efforts was a picture of myself being filmed by a camera crew walking towards a front door. Maybe it was my very own little prediction of what was to come; I don’t know. I always loved cooking, too, right from when I was a little girl, and I remember being in the Brownies, making a mean sausage and mash, which is still one of my favourites. Maybe it’s because my mum has always made the best mashed potato – I guess it’s the Irish in us.

Whatever the time of day, if I had my eyes open, I was always active. Always busy doing something. If I wasn’t playing the piano in the house, I was out in the garden in the mud, trying to find frogs or climbing trees. I always like the option of being able to run away and hide somewhere, to escape. I found myself a little hideaway up a tree at the bottom of the garden; my fortress, I called it. Whenever I was in trouble or Mum or Dad came after me, or if I wanted to be on my own, I’d run to my fortress, high in the tree. It wasn’t an especially complicated structure, but it did have a pulley system, which I’d made myself.

‘Mum, can I have a sandwich, please?’ I’d shout.

Mum would put the sandwich on the pulley, and I’d bring it all the way up to the top of the tree. My fortress was also great for pranks. Sometimes, when we had friends round, us kids would be up in the fortress dropping water bombs on people, like the little shits we were.

What I loved most of all was playing Dad’s guitars. He would re-string them every weekend and let me strum away. I even got my own guitar eventually; a pale-pink Marlin Sidewinder, and, to go with it, a mini Marshall amp. There was nothing I loved more than plugging my little pink guitar in and playing in the corner of the room.

Quite often, you could find me standing in front of the hi-fi, singing along to Mariah Carey or Whitney Houston, just waiting for my dad to come home from the rehearsal studio so I could show my voice off to him. I loved singing along to those big divas, trying to reach the notes that they could. Even then, I felt like I was getting my voice strong, ready for when I became a professional singer.

I guess my upbringing was what you might call unconventional. My mum, dad and I lived in a village called Wraysbury, which is in the Royal Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead, and directly under the approach path of Heathrow airport. I have a half-brother, Dave, who is sixteen years older than me – Mum’s son from a previous marriage. Back then we didn’t really get on with one another, probably because of the huge age gap. He was a member of The Monster Raving Loony Party, which was, and still is, a bizarre satirical political party started by a guy called David Sutch, AKA Screaming Lord Sutch. My brother’s title was Sir Dangerous, and I remember seeing a recording of him from back in the day: Dave and Lord Sutch on cable TV, interviewed by none other than Sacha Baron Cohen.

Another peculiar thing about my childhood was the number of schools I attended. Rather than two, or maybe three schools, like most kids, I went to seven. I know, seven! I wish I could tell you why I went to so many schools, but the truth is I don’t know, not really. What I do know is that I was not an easy child to manage, mainly because from a young age I had ADHD – attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. It’s a condition that affects people’s behaviour, making them appear restless and impulsive. People with ADHD can have trouble concentrating or display signs of manic behaviour, depending on the severity of the individual case. It started when I was tiny, and it would be something I’d have to learn to live with always.

While I was at kindergarten, and at the start of infants’ school, I used to go to see a woman, a child psychologist, who would regularly assess me. At the same time, I played with all the toys in her office. While I invented games, playing happily, she would talk to me and take notes, asking me questions about the games and what was happening in my created world.

Of course, I had no idea why this was happening back then; I assume it was some kind of play therapy to find out what made me tick. I guess my parents needed to find out why I had a seemingly endless amount of energy, which was very much the case; I mean, I was hardly ever sitting down quietly. Usually, I was running around, breaking things or cutting off my doll’s hair. I remember having two Barbies but desperately wanting a Ken so I could marry one of them off. Mum wouldn’t buy me a Ken, so I cut off one of the Barbie’s hair in an attempt to turn her into a bloke. Essentially, at the age of five, I had lesbian Barbies, who were married by the taps of the bath while I was in the tub with an entire kingdom of toys. Eventually, the child psychologist arrived at the ADHD diagnosis. Still, I wasn’t given medication at first because everyone felt I was too young. I didn’t start taking medication until years later when I was in the band and struggling somewhat with the pressures of fame.

So back to the seven schools. I suppose I was feeling a different kind of pressure then; the pressure of constantly adapting to new environments.

I was about nine when my parents sent me to a boarding school called Thornton College in Buckinghamshire. The school had daily students and weekly borders. I was a termly border, meaning I only went home during school holidays. While I was boarding, my mum went to Manchester to do a counselling course at Manchester University. Being a music teacher and a working musician, my dad’s schedule was all over the place, so they thought boarding school was the answer. The college wasn’t that far from where we lived in Buckinghamshire, so, as a child, it was hard for me to grasp why I couldn’t go home more often. It’s something I touched on in therapy later on in life, and something I’ve asked my parents about too. What was going on in their marriage that they couldn’t have me there all the time? I guess I didn’t realise how hard things were for them back then. My mum really missed her family up north and wanted to better herself, and my dad was working all the hours God sent to make money.

Thornton was an ancient building and run by nuns. I wouldn’t say I liked it at all. There was a cavernous room with pillars called the Red Hall, which could be very scary, especially at night when you had to walk across it and couldn’t find the light switch. It was called The Red Hall because a nun had apparently once hung herself from the top of the stairs and blood had dripped down on to the floor. Like most kids, I believed in all the ghost stories I heard, so I was always terrified if I had to cross the musty, cobweb-filled Red Hall on my own. I’d run from one pillar to the other, convinced the ghost of the dead nun would get me.

The good things I remember about the place is having piano and music lessons, which was something to look forward to each week. Also, the fact that there were lots of Spanish girls at the college, which meant I picked up a lot of the language.

Our matron was in her late thirties and looked exactly like Miss Hannigan from Annie, with short hair and a gap in her teeth. I’m not sure why, but she took a dislike to me and also another little girl from Zimbabwe, Rudo, who was the youngest in the school. I was the second youngest. I never knew why, she just wasn’t very nice to us, which made my experience pretty miserable.

We slept in dorms where we also played marathon card games at weekends, and we all ate in one big hall. Some nights, Rudo and I would steal out of bed so we could go and chat with the other girls. A few times we got caught, and Matron would make us stand in the corridor, facing the wall for hours. It was pretty brutal.

I wasn’t aware of it at the time, but I’d only got into the school because I’d passed several tests and been awarded a bursary. The school fees were expensive, and my parents would never have been able to afford to send me there had I not been bright. God, if I’d known that, I would have played dumb, flunked the bloody exams and gone to a regular school.

My half-brother Dave was the only one who ever visited me at Thornton. He turned out to be a bit of a hero, and in more ways than one.

It all started when he came to one of the school’s disco nights, which I ended up getting kicked out of. I know, can you imagine? Nine years old and thrown out of my first disco! What could possibly have been the reason, you might ask. We

ll, I’d recently seen the movie Dirty Dancing. I thought it would be a rather excellent idea to try out some of the provocative, grinding moves I’d learned from the film, at a disco full of pre-teen girls. The nuns weren’t happy, despite my brother explaining that I was only a kid copying what I’d seen in the movie.

‘No, it’s not on,’ Matron had said. ‘Get her out!’

I was unceremoniously hauled away, while Dave went on to try to reason with her. In the end, she invited him ‘for coffee’ that evening and, strangely enough, after that night, she was a lot less horrible. In fact, she never said a bad word to me and was sometimes even nice. I didn’t know it at the time, but it seems my brother’s coffee may have turned into something more than just coffee. It’s possible he’d taken one for the team!

Despite the change in Matron’s attitude, I still wasn’t happy. I was constantly homesick and missed my parents. All in all, I was at Thornton for a year, and it was a lonely, tough year. During my time there, I began to have panic attacks and stopped eating properly because I was so anxious all the time, so I was thrilled to be out of there. Still, there was more unhappiness to come.

I was offered a place at a prep school called St Mary’s, but Mum and Dad found out that the deputy head of Thornton was taking over as head at a school called Godstowe, where I could also board. I think my parents thought that my ex-deputy head might show me some favour and look after me, but it didn’t really work out like that. I remember my dad driving me to Godstowe, trying to be terribly enthusiastic. He and his brothers had gone to boarding school, which Dad seemingly loved and hated in equal measure. Dad’s father had been a doctor in the RAF during the Second World War and a practising GP after that. His mum– my granny – was a quite middle-class lady who played the piano beautifully.

Hear Me Out

Hear Me Out